Evaluating Electrochemical Reversibility

Reversible Waves

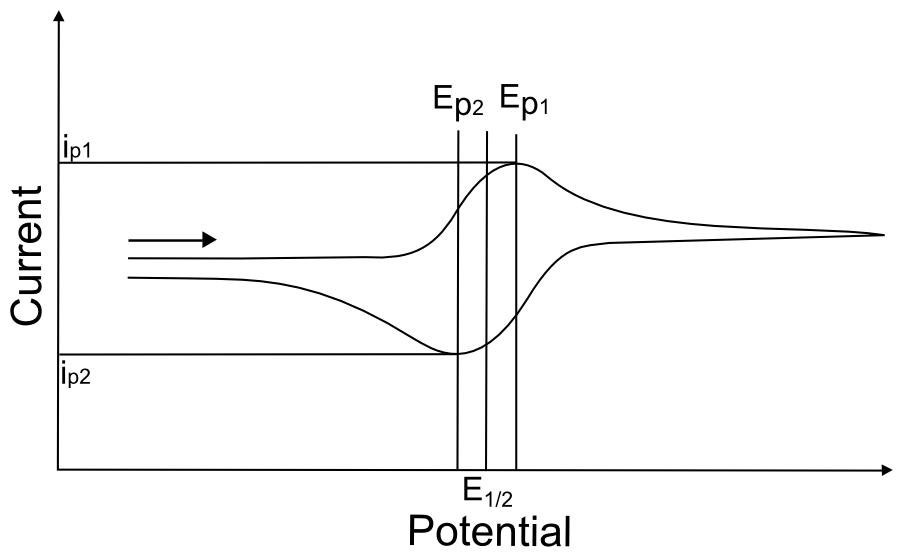

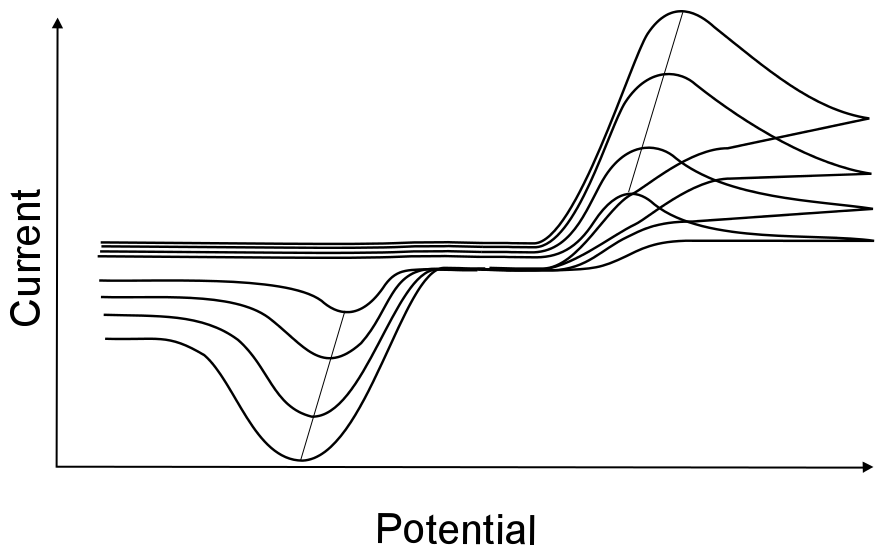

For a reversible wave, one can easily determine all of the wave characteristics listed in the previous section, including the E1/2, the Ep’s, and the ip’s. It is easy to verify that the wave is in fact reversible by simply looking at the separation of the two peaks of the wave, which should be about 60 mV apart. If they are much further apart, it might indicate that the wave is not reversible, that the electrode was not properly polished, or that the solution resistance was not properly compensated. The most certain way to tell if a wave is reversible is to observe that the Ep’s remain constant with varying scan rate.

hover over pic for description

Irreversible Waves

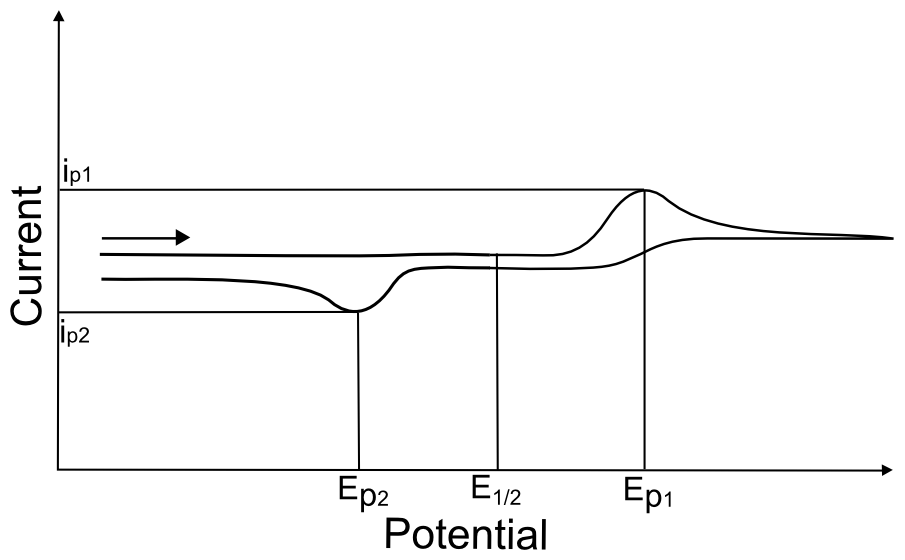

The appearance of an “irreversible wave” could be due to either an irreversible (slow) electron transfer, or an electron transfer (either slow or fast) followed by a chemical step that transforms the product of electron transfer into another species. When a reduction wave is hundreds of millivolts away from an oxidation wave, there is no easy way to prove that they are the result of a single X/X– redox couple. The best proof would be for both species (X and X–) to be isolated and characterized independently, to prove that they are relatively stable in solution.

hover over pic for description

A basic understanding of the chemistry of the analyte (whether it can act as a Brønsted-Lowry acid/base, whether it can gain or lose a ligand in a different oxidation state, whether it can react with another molecule in solution, etc.) can allow one to infer the cause of irreversibility. For instance, if the analyte is a metal complex that has 6 ligands, and the only orbitals on the metal that can accept electrons are anti-bonding with respect to the ligands, the loss of a ligand upon reduction might give rise to an irreversible wave. On the other hand, if the structures of both the +2 and +3 oxidation states of a metal complex are known to be coordinatively identical and stable in the electrolyte solvent, yet the reduction wave is irreversible, it is safe to guess that the electron transfer is just slow (is electrochemically irreversible) and there is no reason to suspect a follow up chemical step. Below are some common ways to determine whether the irreversible wave is just due to an irreversible electron transfer or an irreversible chemical step.

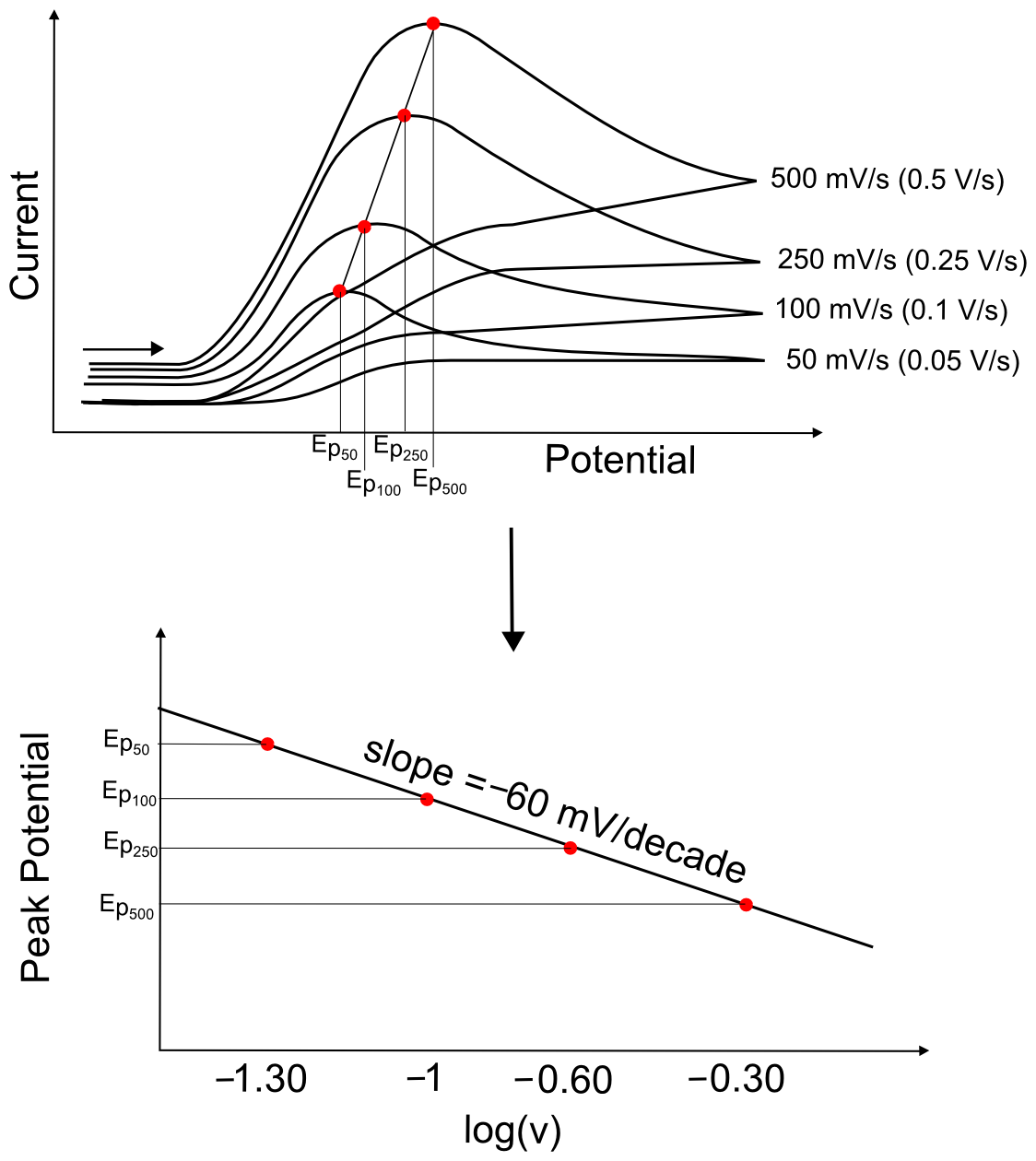

Irreversible Electron Transfers

Assuming that it is a single electron transfer, collecting CVs at a variety of scan rates and plotting Ep vs. the logarithm of the scan rate (log(ν)), where v is in volts per second (V/s), should fit a straight line with a slope of (+/–)60 mV/decade (where a decade is an order of magnitude, or each integer on a log scale). If the slope does not equal 60 mV/decade, it could be due to a follow up chemical step (which will be discussed in the next section), but could also be due to other factors which are beyond the scope of this text.

hover over pic for description

Demonstrating Electrochemical Reversibility

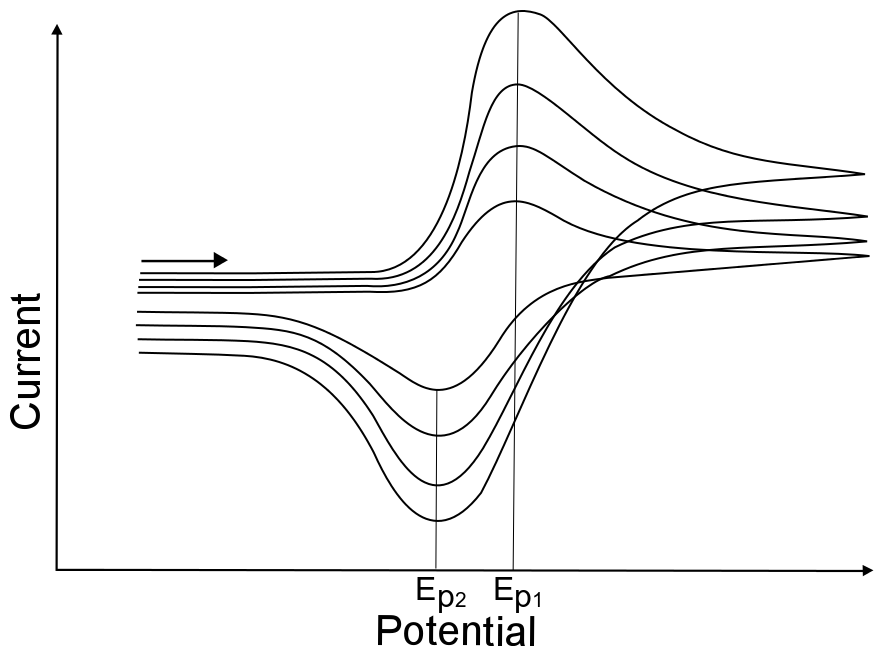

The change of peak potentials with scan rates is very telling about the nature of the electron transfer. For a completely reversible electron transfer, the peak potential will not change with scan rates.

hover over pic for description

This is because the electron transfer rate constant in a reversible electron transfer is so fast that diffusion of the analyte is the only factor that determines the peak potential. The peak potential for a reversible wave remains the same because the concentration of X and X– at the electrode change instantly with every small change in electrode potential, regardless of scan rate. This results in the occurance of the maximum concentration gradient of X (which is when the maximum current is observed) at the same potential. Even though the maximum concentration gradient occurs at the same potential, the magnitude of this gradient increases with increasing scan rate, resulting in an increase of peak current with increasing scan rate.

hover over pic for description

Irreversible waves, however, will show a change in peak potential with increasing scan rate. This is because the electron transfer rate constant is slow, meaning that more extreme potentials are needed to induce electron transfer. If the scan rate is increased, the concentration gradient takes longer to react to the change in potential, and the maximum concentration gradient occurs at potentials further and further from E0. For most irreversible electron transfer, plotting the peak potential vs. log(ν) will give a slope of about 60 mV/decade.

Did I earn one of these yet?

is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.