Effects of Chemical Steps

Nomenclature

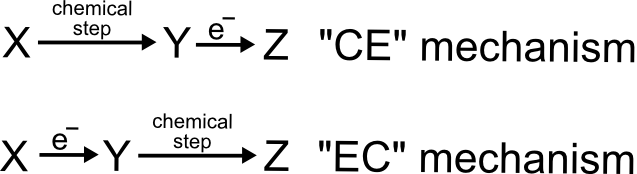

We need to differentiate between the different orders in which the electron transfers and chemical steps can occur. To do this, the community has adopted the abbreviations of “E” and “C” to represent an electron transfer chemical and a chemical step, respectively. For example, if we identified a process in which a chemical step has to occur first and is followed by an electron transfer, we refer to it as following a CE mechanism, whereas an electron transfer followed by a chemical step is an EC mechanism. It is possible for these to get quite complicated with multiple electron transfers and chemical steps, but we will stick to the basics.

hover over pic for description

Chemical Step Followed by an Electron Transfer

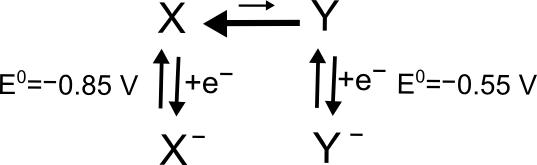

When an electron transfer is only possible following some chemical step, it is referred to as a "CE mechanism." Let’s take an example where analyte X is in chemical equilibrium with Y so that there is much more X than Y. Let’s also assume that we know the standard potential of both the X/X– and Y/Y– couples, where E0(Y/Y–) = –0.50 V and E0(X/X–) = –0.85 V. In solution, there is always a small concentration of Y as determined by the X/Y equilibrium.

hover over pic for description

A real life example of this type of problem might be an acid base equilibrium. If Y is just protonated (and positively charged) X, then it should be easier to add an electron to the positively charged species (Y) than it is to add an electron to the neutral species (X).

hover over pic for description

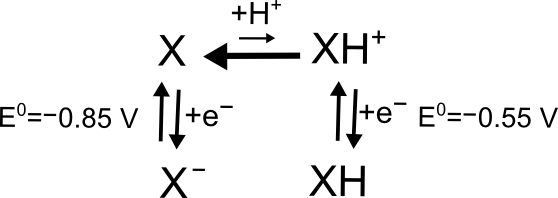

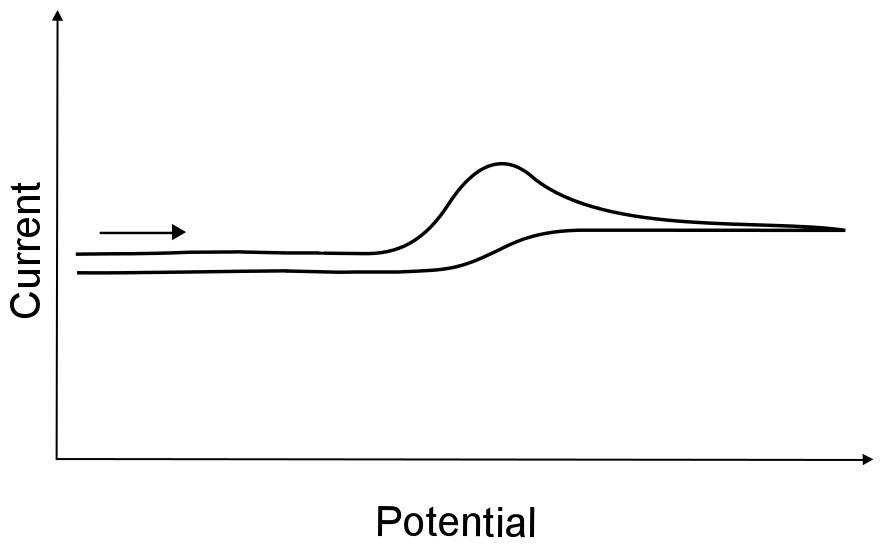

As the potential approaches the Y/Y– reduction potential a small increase in current is observed and the “peak” of this wave, if it is even apparent, is small and indistinct. If the current is reversed after this wave, however, one might observe a large, “regular” oxidation peak. This is because a significant portion of Y– was able to build up when the electrode potential was more negative than the Y/Y– reduction potential. If Y– is stable in solution, when the electrode returns to the Y/Y– reduction potential, the potentiostat will register current from the oxidation of Y–, resulting in a CV like this.

hover over pic for description

Electron Transfer Followed by a Chemical Step

Occasionally, a chemical process will occur after an electron transfer, which is described as an EC mechanism. To add to the confusion, sometimes the species that results from the chemical step can undergo an additional electron transfer, which is referred to as an ECE mechanism. There are various ways to try and figure out when the chemical step is occurring and if another electron transfer occurs. We will outline some common methods for quickly interpreting CV traces.

EC Mechanism

Sometimes, an electron transfer is followed by a chemical process that changes the molecule in such a way that a return wave is not observed. This will result in a current observed on the forward sweep while no current is observed on the return sweep. A common way to check whether this is the case is to increase the scan rate and hope that the chemical step is slow enough that a fast scan rate will be able to catch some of the product of the electron transfer before it has a chance to decay. Other times, a reversible wave can be made chemically irreversible with the addition (or withdrawal) of another species from solution. This wave is often referred to as an irreversible wave, not because the electron transfer is irreversible (fast), but because the follow up chemical reaction is chemically irreversible.

hover over pic for description

Multi-electron Processes - ECE/DISP Mechanisms

Sometimes, the product of an electron transfer takes part in a chemical process resulting in a molecule that can undergo another electron transfer. For this mechanism, known as ECE, there are two possible scenarios; the new molecule is either easier or harder to reduce than the parent molecule. We can illustrate this with a variation of the X/XH+ example used above, except where the X ⇆ XH+ equilibrium is non-existent, but XH can be reduced a second time to become XH–. Integrating the curve under a wave in a CV is not a legitimate way of 'counting' the number of electrons transferred, the current depends on a variety of other factors, not just the number of electrons transferred.

hover over pic for description

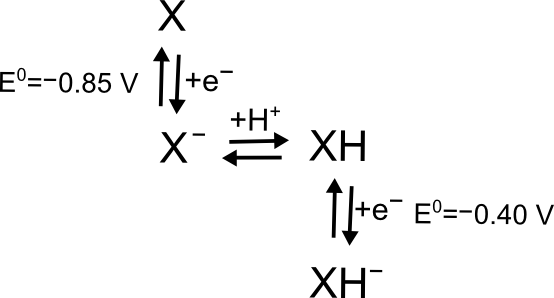

X + e– ⇆ X– has a reduction potential of –0.85 V. X– may undergo a chemical step, reacting with a proton (H+) to form XH. XH has its own reduction potential for the reaction XH ⇆ XH–, which can occur at a potential more positive or more negative than the X/X– reduction potential. If the XH reduction potential is more positve, say –0.40 V, it will immediately accept another electron from the electrode, since it was brought into being at a potential far more negative than its reduction potential. This overall process will look like a two-electron reduction, but it is not a true concerted two-electron transfer, as there was a chemical step between them.

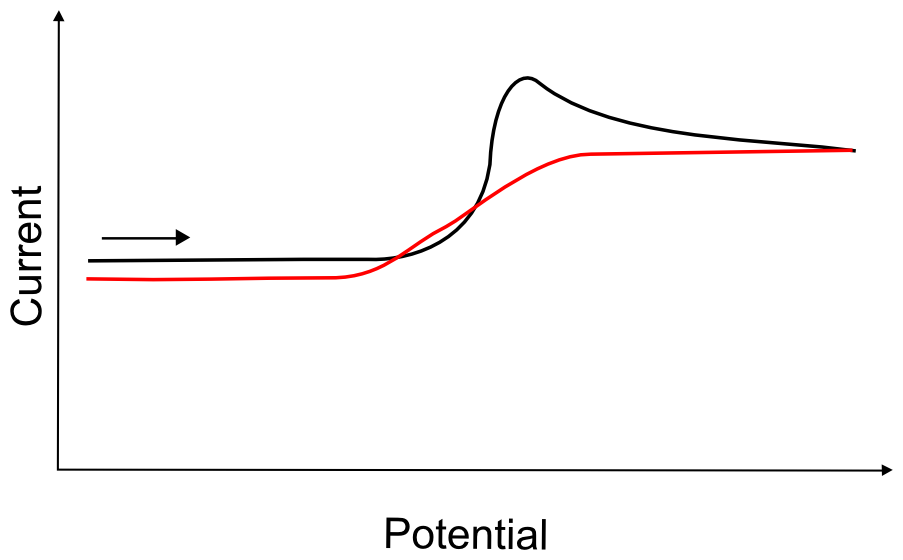

Sometimes, if the chemical step is slow enough to be out-paced by the scan, the ECE mechanism will give rise to trace crossing. Trace crossing is exactly what is sounds like; after a feature in a CV, when scanning back past the potential of that feature, there is more current observed than is expected.

hover over pic for description

This is due to the fact that (using the example given above) while X– is generated at the electrode, it may travel away from the electrode before it reacts with a proton (H+). Now there is a small concentration of XH in solution that begins to diffuse back towards the electrode. Even if the potential sweep reverses direction and travels back to a potential where no more X– is produced, any XH that finds its way back to the electrode before its potential decreases far below –0.40 V will be reduced, giving rise to a reduction current where there was not any on the forward sweep.

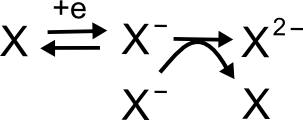

Another mechanism that looks like an overall two electron process is disproportionation. In a disproportionation reaction, X is reduced to X–, but when two molecules of X– meet in solution, they transfer electrons to make one X and one X2–. The net reaction is the two electron reduction of X to X2–.

hover over pic for description

This disproportionation mechanism is similar to the ECE mechanism in most respects. There is one way to differentiate between the two, it is beyond the scope of this book, but it can be found in Savéant.

Electron Transfer Coupled to a Chemical Step

The concept of proton-coupled electron transfer (PCET) or concerted proton-electron transfer (CPET) has been a popular subject of study. In short, is describes electron transfers that occur as a proton is being transferred, and is not quite and EC or a CE mechanism. As the names imply, this type of reaction usually occurs in the presence of protons, either added intentionally or from the solvent. Since the effect involves the "tunneling" of a proton, one popular way to test whether an observed electron transfer is proton coupled or not is to replace all the protons with deuterons using deuterated solvent or acid. If the electron transfer is truly coupled to proton transfer, a massive deuteron should transfer more slowly, and therefore electron transfer should slow down (or shift to a more extreme potential). This change in rate when different isotopes are used is also known as the “kinetic isotope effect.” If a kinetic isotope effect is observed, it might indicate a proton-coupled process, but further analysis of these systems are beyond the scope of this text.

Did I earn one of these yet?

is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.