The Nernst Equation

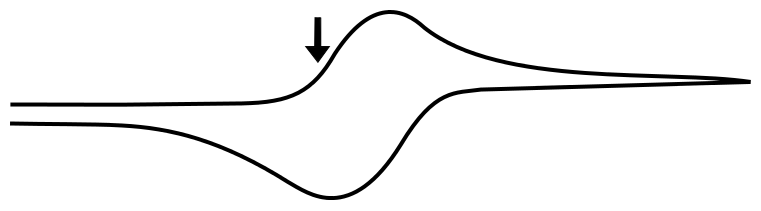

Knowing how the Nernst equation was derived, while beneficial, is not necessary to collect and interpret CVs. The Nernst equation was not derived with cyclic voltammetry in mind, but it applies in the case of a reversible electron transfer. In the following discussion we refer to an analyte X that can be reduced to X–, we assume that the X/X– couple is electrochemically reversible, and that both species are infinitely stable in solution.

The Nernst equation can be used to determine the relative concentration of X to X– at the electrode at every electrode potential (E) encountered on the sweep (if the wave is reversible). The requirement that the electron transfer be reversible (fast) is to ensure that electrons are transferred rapidly and equilibrium is always maintained at the electrode. In other words, the concentrations of X and X– at the electrode change immediately as the electrode potential changes. This is the origin of the term “electrochemically reversible,” just as we say that the expansion of a gas is “reversible” if equilibrium is maintained during the (incredibly slow) expansion of a piston, electrochemical reversibility means that electrons are exchanged so rapidly and the equilibrium concentrations (determined by the Nernst equation) are maintained at all points during the potential sweep.

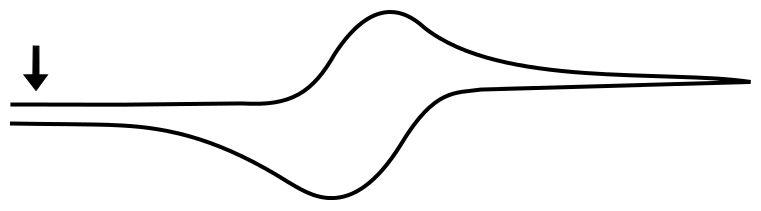

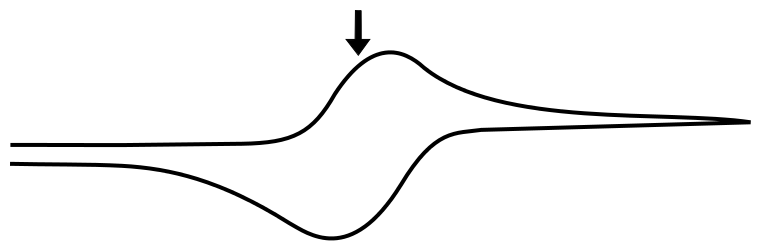

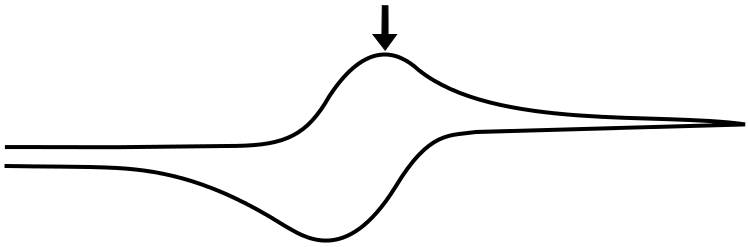

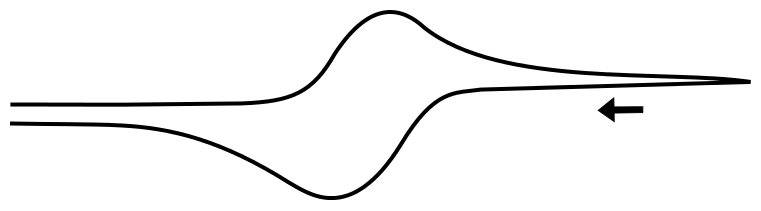

hover over pic for description

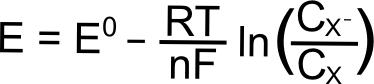

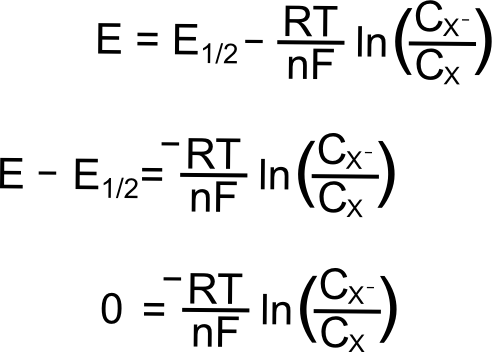

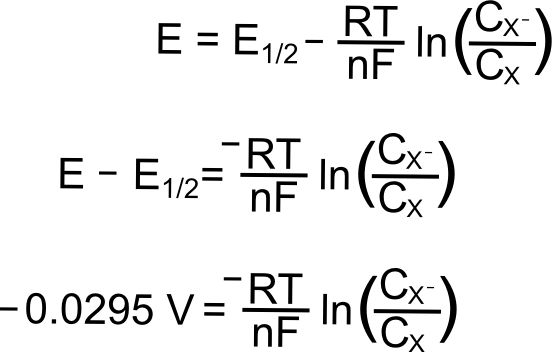

For the electrochemically reversible electron transfer X + e– ⇆ X–, the Nernst equation is written as follows:

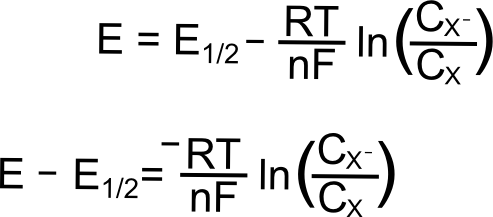

Where E is the electrode potential (in Volts), E0 is the standard reduction potential of the X/X– couple (in Volts), R is the gas constant (8.315 J K–1 mol–1), T is the temperature (in Kelvin), n is the number of electrons transferred (1 in this case), and F is Faraday’s constant (96,485 C mol–1), and CX (or CXˉ) is the concentration of the respective species (X or X–) at the electrode (mol L–1). In most cases, one can assume that the E1/2 that is measured for a reversible wave is equal to the E0, and we will use E1/2 from here on.

During a CV of a reversible wave, we will be changing E and electrons will transfer between the electrode and the analyte to change the concentrations of X and X– accordingly. It is important to remember that we are only concerned with the concentrations of the species at the electrode, which can differ from the concentration of the analyte in bulk solution.

Part of this equation, namely the relation between the species in the reaction and the fraction CXˉ/CX (the reaction quotient), might look very familiar to those of you who have calculated acid/base equilibria. This should serve as a reminder that the Nernst equation is an equilibrium equation, and that the electron transfer during an electrochemically reversible wave should be viewed as a fast electron transfer to AND from the analyte and the electrode; where the electrons reside on average depends on the electrode potential.

Let us illustrate this relationship between concentrations of X and X– at the electrode and electrode potential with some obvious examples. We will talk about what is happening next to the electrode at a variety of potentials during the CV scan in a solution of X.

Before the Wave

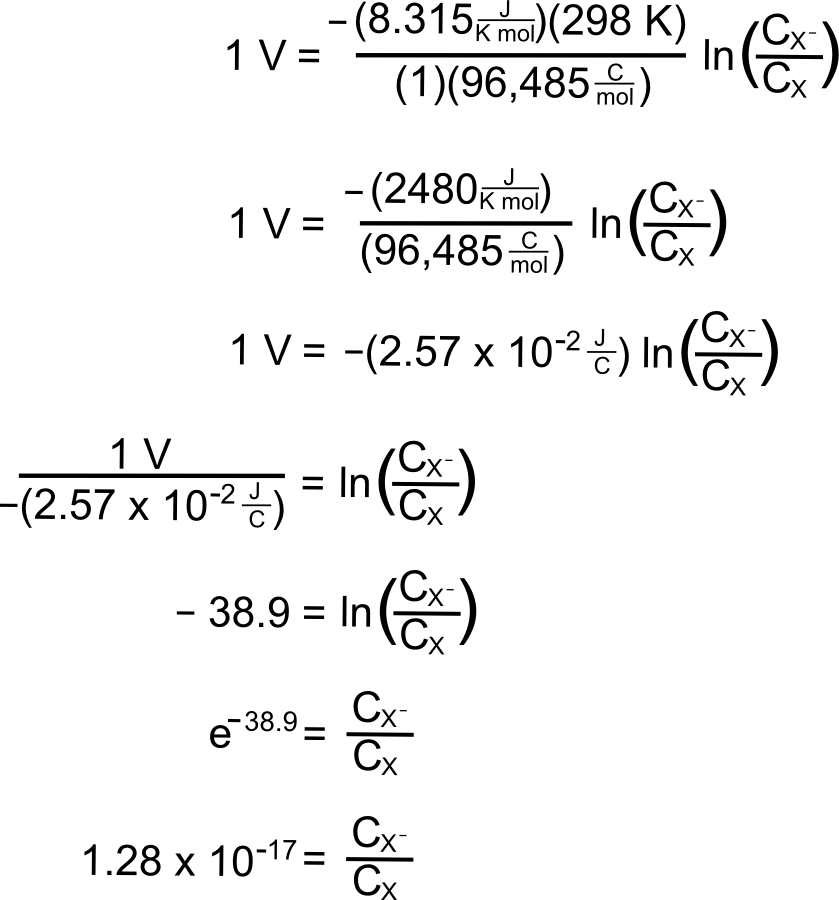

We begin with the electrode potential 1 V more positive than the E1/2 of the X/X– couple. At this potential, effectively all of the analyte is in the form of X. We can calculate the fraction X/X– at the electrode predicted by the Nernst equation as follows. The exact value of the potentials is not needed for the calculation, since we know that the electrode potential is 1 volt (V) positive of E1/2(X/X–), the value of (E – E1/2) is 1 V. Remember that a volt is a joule per coulombe (J/C). Rearranging the Nernst equation gives us a way to find the ratio of X–/X.

Plugging in the known values (assuming a temperature of 298 K), we get

meaning that in a solution containing 1 mM (0.001 M) of X, there will be a concentration of 1.28 x 10–20 M of X– at this potential, an almost incomprehensibly small yet non-zero amount.

Foot of the Wave

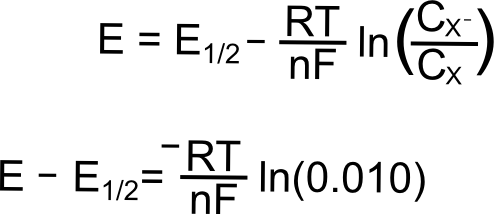

As the potential scans more negative, at some point observable current begins to pass between the analyte and the electrode. Even though we are still at a potential more positive than the standard reduction potential of the X/X– couple, a non-negligible amount of X– begins to appear at the electrode. Let us calculate at what potentials we would find that 1% and 25% of the analyte is reduced (to X–). We will start with the Nernst equation, use 0.010 and 0.25 for (CXˉ/CX), and find (E – E1/2).

Potential where 1% of the Analyte is Reduced

plugging in the known constants, we get

So at a potential 120 mV (0.12 V) more positive than E1/2, 1% of the analyte at the electrode is in the reduced form, X–.

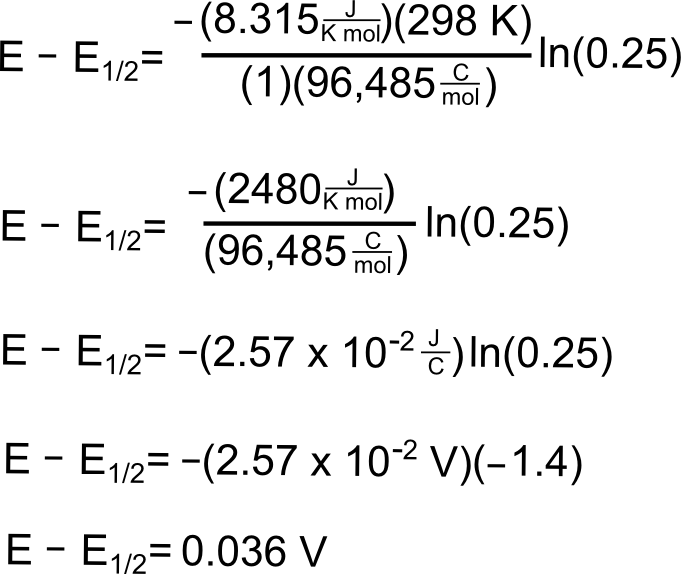

Potential where 25% of the Analyte is Reduced

To find the potential where 25% of the analyte is in the reduced form, we follow the same procedure except we use 0.25 for (CXˉ/CX).

So we see that at a potential 36 mV (0.036 V) more positive than E1/2(X/X–), 25% of the analyte is reduced.

E1/2(X/X–)

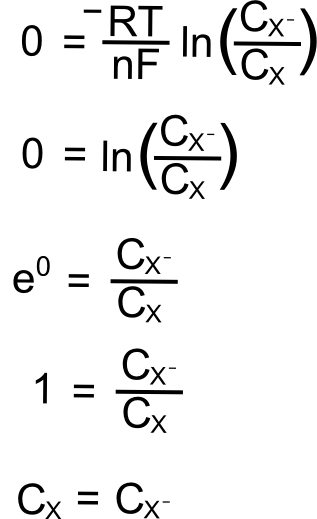

For a reversible couple, E1/2 is E0 (if we assume that X and X– diffuse to and from the electrode at the same rate, not so bad of an assumption for most redox pairs). This greatly simplifies our problem when the electrode potential (E) is at the analytes reduction potential (E1/2) since E = E1/2 = E0 and (E – E0) = 0.

Removing the constants (since we multiply them by 0), we get

So at the E1/2, the concentration of X at the electrode is equal to the concentration of X– at the electrode!

The Peak

The peak of the wave is by definition the point of maximum current, but what is significant about this point of the sweep in terms of the relative concentrations of the analyte species? The answer is... nothing. For an electrochemically reversible wave at 298 K, the peak is 29.5 mV past E1/2. We can find the concentrations of X and X– at this point using the Nernst equation and the fact that the quantity (E – E1/2) = –0.0295 V (for a reduction). For an oxidation, (E – E1/2) would be +0.0295 V.

plugging in the known values, we get

So at this potential, the concentration of X– is 3.16 times than X. These concentrations alone do not explain the shape of the CV curve, for that we will need to take into account diffusion of the analyte. In an electrochemically reversible reaction such as the X/X– couple, electron transfer is much faster than diffusion, which means that the rate of diffusion determines the shape of the wave and where the peak occurs.

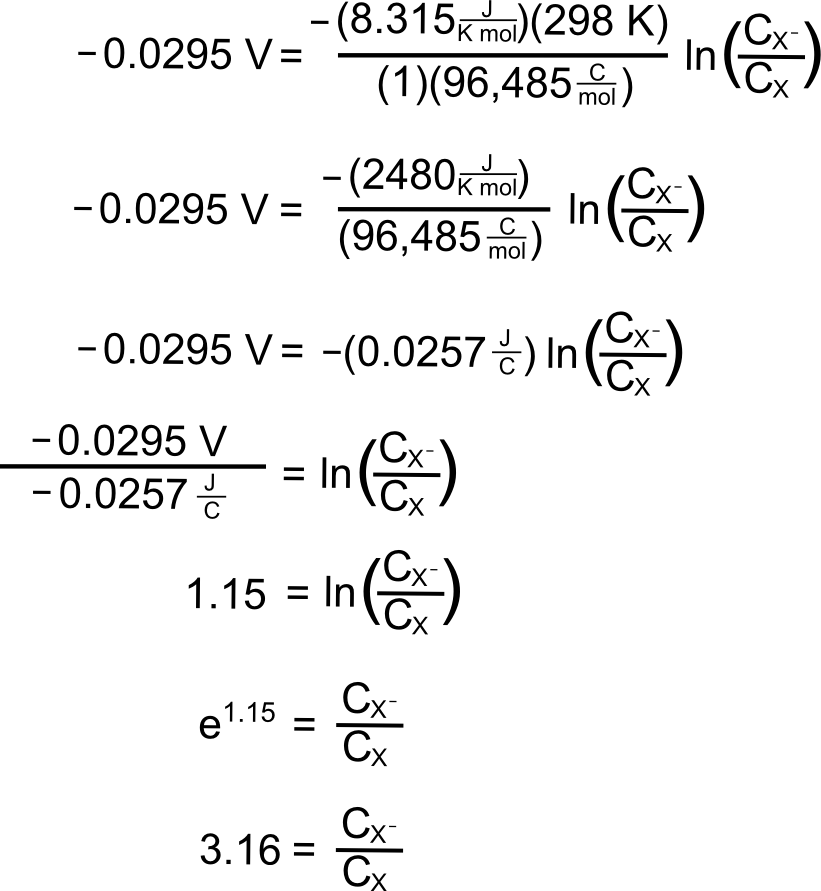

After the Wave

When the electrode potential passes the peak of the wave and travels far past E1/2, it reaches a point where the current remains relatively constant with increasing potential. The value of the current in this region is known as the limiting current, ilim ( or mass transport limited current). This is because any analyte that reaches the electrode is immediately reduced, and the current (electrons transferred per unit time) depends only on the rate at which the analyte is transported to the electrode by diffusion.

We don't have to go through the exercise of calculating the concentrations if we realize that the concentration of X at the electrode when the electrode potential is 1 V more negative of E1/2 is identical to the concentration of X– at the electrode when the electrode potential is 1 V positive of E1/2, 1.28 x 10–20 M (in a 1 mM solution of analyte). This concentration is effectively zero, which begs the question "why do we see an observable current when the concentration of the species being reduced is effectively zero at the electrode? The answer is discussed in more detail in the next section, Transport of Molecules in Solution.

The Return Scan

When the direction of the potential sweep is reversed and the potential of the electrode approaches and then surpasses E1/2, the same process happens in reverse. The concentrations of X and X– reverse and return to normal, with the peak occuring 29.5 mV more positive than the E1/2, giving rise to the familiar shape of a reversible wave.

Did I earn one of these yet?

is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.