Electrochemical Potential

Electrochemical Potential of the Analyte

A long explanation of chemical and electrochemical potential often occurs at this point in an explanation of thermodynamics of electron transfer, but a qualitative explanation is possible given a few facts which will now be introduced. When we talk about electrochemical potential of an analyte, we are thinking of a collection of redox-active analyte molecules. Let's call this molecule "X," which can be reduced through addition of an electron to the species "X–." X and X– have different potential energies, and since the potential energy of a reduced species is higher than that of its neutral counterpart, X– has a higher potential energy than X. Imagine that we can create a solution of X and X–, the potential energy of that collection of X and X– can be changed by varying the relative amounts of X and X–. This relationship is described using the famous Nernst equation.

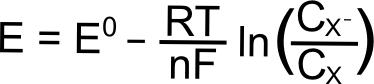

hover over pic for description

Hopefully some of the constants in the Nernst equation look familiar, R is the gas constant (8.315 J K–1 mol–1), T is the temperature (in Kelvin), n is the number of electrons transferred (1 in this case), F is Faraday’s constant (96,485 C mol–1), and CX (or CXˉ) is the concentration of the respective species (X or X–) in solution. E0 is known as the "standard reduction potential" of the reduction of X to X–. This value is calculated at 1 M concentrations at standard temperature and pressure, but for our purposes, we can assume that this value is equal to the E1/2 of the X/X– reduction measured in a solution with analyte concentrations much much lower than 1 M. The "E" on the left side of the equation is the electrochemical potential of the collection of X and X– molecules in solution. If we were to make a solution with 1 mole of X and 1 mole of X–, the electrochemical potential energy of the collection of X and X– molecules in solution will equal E0 (which is also E1/2).

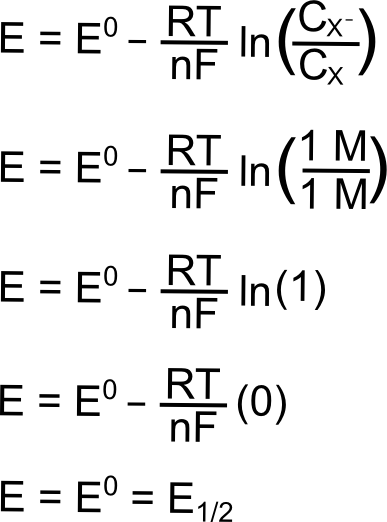

hover over pic for description

The next section contains some examples of how the electrochemical potential of the solution changes when plugging in some other example ratios of X and X–, but one can see from the equation above that increasing X relative to X– moves the electrochemical potential of the solution more positive than E0 (lower potential energy), while increasing X– relative to X moves the electrochemical potential more negative of E0 (higher potential energy). Knowing this, we can represent the effect of changing the ratios of X and Xˉ on both a potential energy scale and a solution potential scale.

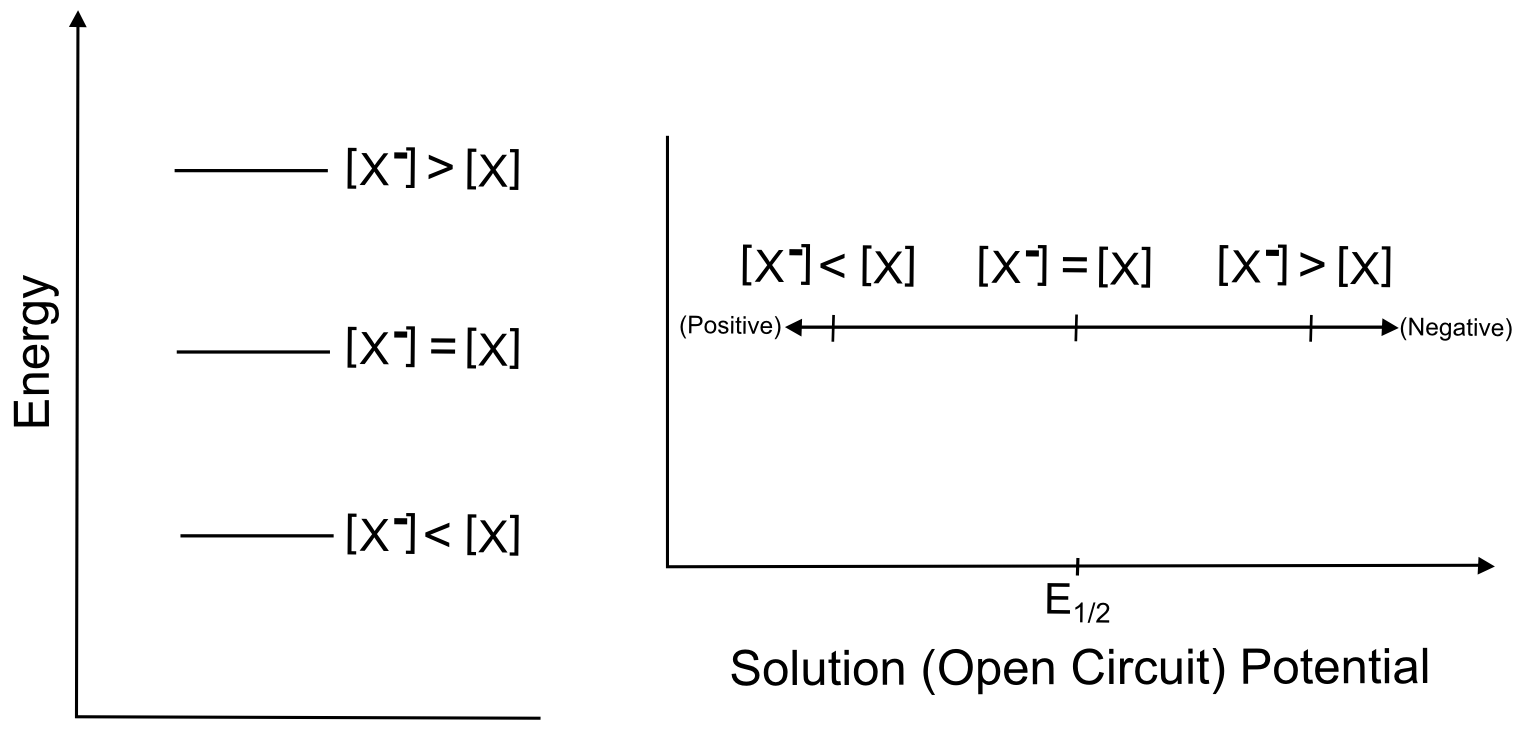

hover over pic for description

So in our theoretical beaker with our imaginary solution, changing the relative ratios of X and X– change the electrochemical potential, but this example is not directly applicable to cyclic voltammetry. In a typical CV, when we transfer electrons between the electrode and the X/X– molecules, the relative ratios of X and X– change in the microscopic area directly next to the electrode. Incredibly, this is all we need in order to observe the changes that result in a CV, which is why cyclic voltammetry is often called a "non-destructive" technique.

Electrochemical Potential of Electrons in an Electrode

As opposed to the electrochemical potential of the analyte, which can be varied over a narrow range by changing solution conditions or concentrations, the researcher has ultimate control over the potential energy of the electrons in the electrode, because "the potential energy of the electrons in the electrode" can really just be thought of as the "potential" or "voltage" of the electrode. We vary this electrochemical potential of the electrons in the electrode over the course of a cyclic voltammogram in order to create the scan. Using a potentiostat and software, we can control the rate at which this electrode potential changes.

For the purposes of this text, it is sufficient to think of the electrode as a solid consisting of a lattice of atoms surrounded in a sea of electrons. We can raise and lower the potential energy of this sea of electrons using the potentiostat. If you're familiar with the band theory of solids, you can think of the act of changing the potential of the electrode as moving the Fermi level up or down to bands of different energies. Even if you're not familiar with band theory of solids, this section can be understood by just knowing that changing the potential of the electrode is really changing the potential energy of the electrons in the electrode. We define positive potential as decreasing the electrochemical potential of the electrons in the electrode so that electrons are more and more likely to jump to the electrode from a species in solution (oxidation). Likewise, one can increase the electrochemical potential of the electrons in the electrode by applying negative potentials, making electrons more likely to be transferred from the electrode to a species in solution (reduction).

hover over pic for description

Did I earn one of these yet?

is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.