Electrochemical Reversibility

The most common way of characterizing features in a CV is in terms of electrochemical reversibility, a concept that is confusing to many. Reversibility does not mean what you think it means; qualifying something as reversible might suggest that an electron can be added to and removed from a redox active molecule, but it does not. Electrochemical reversibility describes the rate of electron transfer.

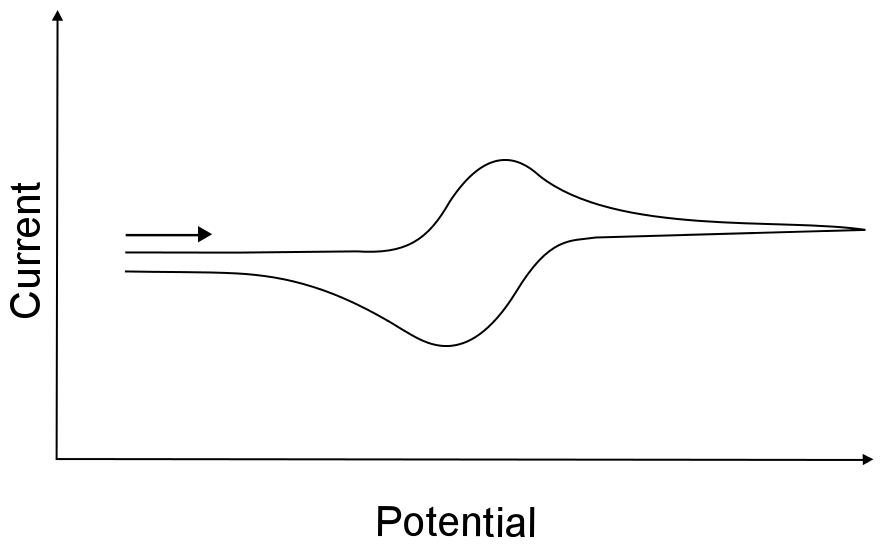

Reversible Electron Transfer

Assuming that both the reduced or oxidized forms of the analyte are infinitely stable in solution, a reversible wave arises when the electron transfer rate is very high (fast). Remember, a fast rate does not mean that the electron transfers between the electrode and the analyte at high speed, but rather electron transfer is "easy" and occurs frequently whenever an analyte molecule approaches the electrode. This "easy" electron transfer results in a CV feature seen below.

hover over pic for description

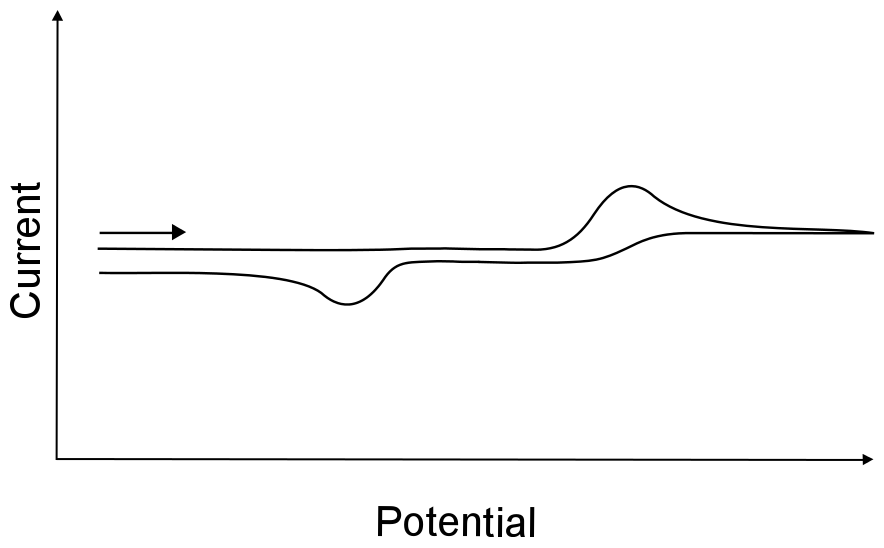

Irreversible Electron Transfer

If the electron transfer rate is slow, extreme electrode potentials are needed to drive the electron transfer and register current on the potentiostat. This is known as an irreversible electron transfer. If X can be transformed into X– as a result of an irreversible electron transfer, and X– can be turned back into X upon scanning back to more positive potentials, the electron transfer is still deemed irreversible (even though the process is "reversible" in a chemical sense). In other words, just because all the electrons that leave the electrode are recollected on the return scan does not mean that the electron transfer was reversible.

hover over pic for description

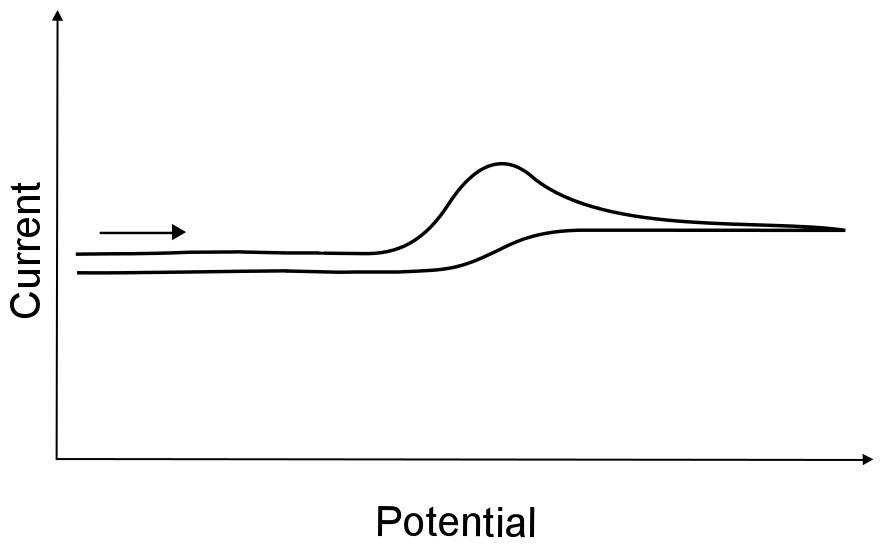

Chemical Transformations of Electron Transfer Products

To further the confusion, the term irreversible wave is sometimes used to describe electron transfers that are followed by a chemically irreversible process, resulting in a single wave with no return wave. Sometimes a return wave is observed, but unless you know that both the oxidized and reduced form of the analyte are stable in solution, there is no way of telling whether the return wave is the other half of an irreversible wave, or just another electron transfer to whatever resulted from the chemical reaction after the first event. For example, if X is reduced to X–, but X– undergoes an irreversible chemical reaction to become Y, one may not see the return wave for X– being oxidized back into X. If a return wave is observed, it may be due to the oxidation of Y, and not necessarily the oxidation of X–.

hover over pic for description

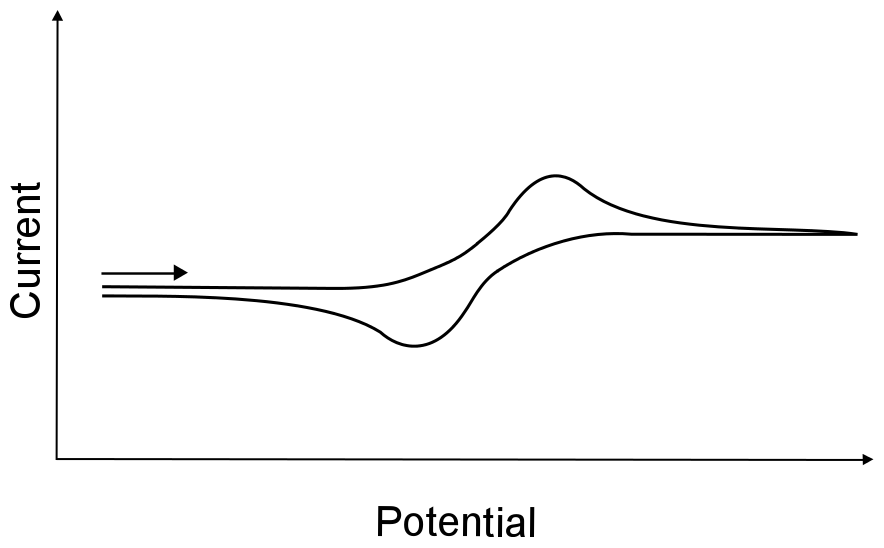

Quasi-reversible Electron Transfers

There is one more term that is often given to electron transfers that fall between completely irreversible and completely reversible, which is quasi–reversible (also known as "quasi-irreversible"). There are loose guidelines that differentiate quasi-reversible from irreversible (which will be discussed in the second part of the book), but it usually up to the researchers discretion. Be careful in assigning a wave as quasi-reversible, what looks like a quasi-reversible wave could actually be a reversible wave collected with an “dirty” electrode that wasn’t polished correctly or has been used for too long.

hover over pic for description

Someone trying to sound fancy might say that a redox couple has either a fast (reversible), slow (irreversible), or intermediate (quasi-reversible) electron transfer rate constant (or heterogeneous rate constant).

Did I earn one of these yet?

is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.