Catalysis

There are whole books written on electrocatalysis, much more than can be covered here. This is an attempt to give beginners enough information to do an initial screen and know where to look for next steps, but researchers often spend years using complicated analyses to investigate the details of an electrocatalyst to figure out its mechanism, rate of catalysis, and ways to improve them.

What is Catalysis?

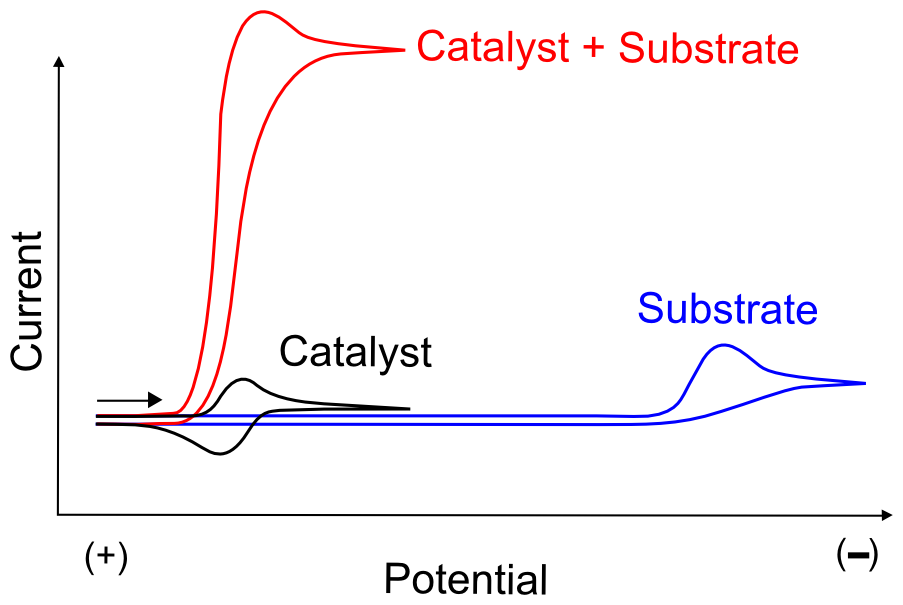

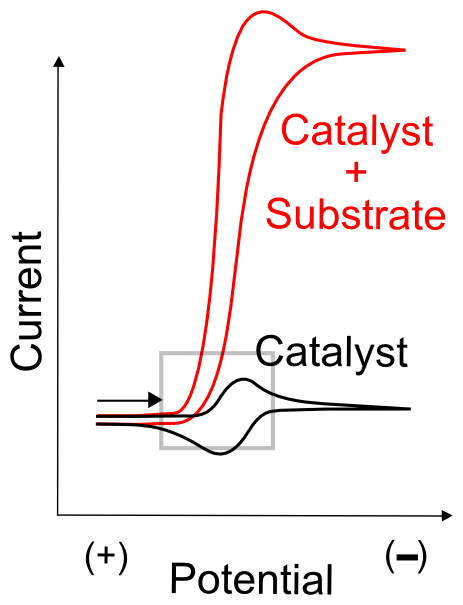

In the electrochemical sense, a catalyst will induce an electron transfer to a substrate at a mild electrode potential, without being consumed or destroyed. For example, assume we have a substrate molecule in solution that we want to reduce by one electron, we collect a CV of it and see that it begins to accept electrons from the electrode at an extreme negative potential. Also assume we know of a molecule which we think is a candidate for catalyzing this electron transfer to our substrate, we collect a CV of it and see that it has a reversible electron transfer at a potential much more positive of our substrate. If we then make a solution of our catalyst and an excess of our substrate, we might see a large increase in current when our working electrode approaches the E1/2 of our catalyst molecule, indicating that once the catalyst gets reduced by the electrode, it then transfers the electron to our substrate molecule, thereby facilitating the overall reaction of substrate reduction at a more mild potential.

hover over pic for description

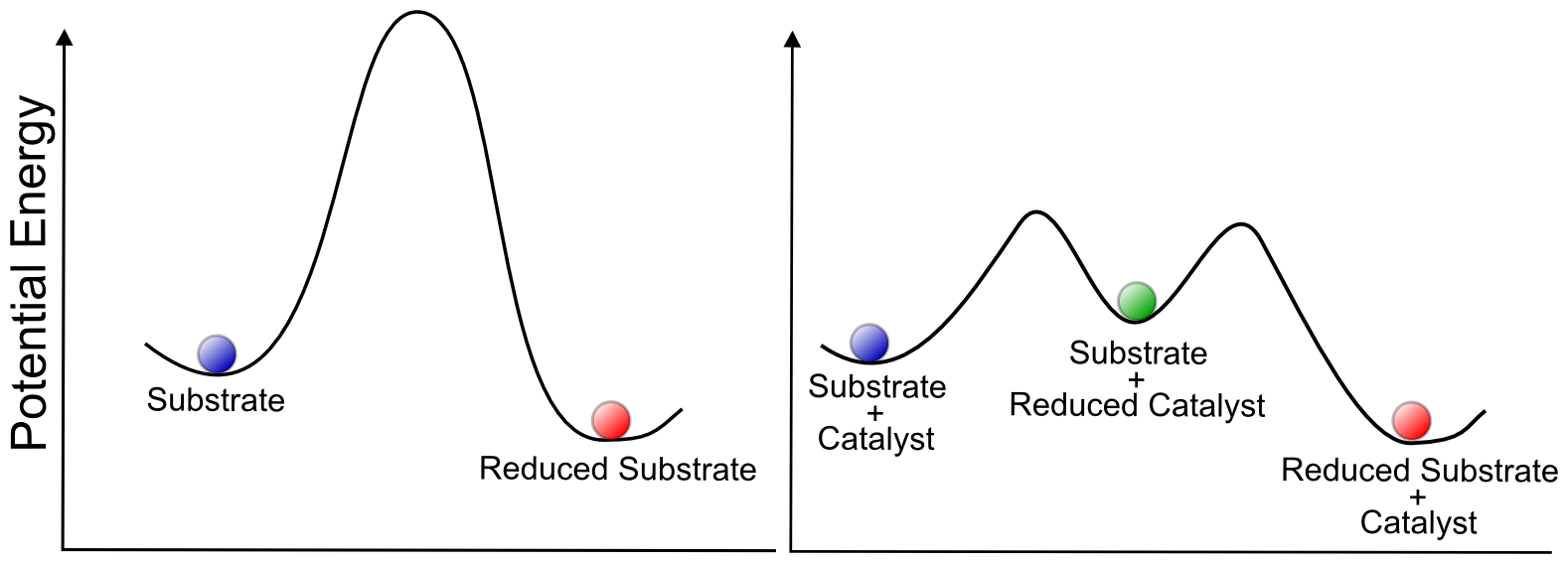

In terms of our potential energy "hill and valley" representation of reactions, we can interpret the role of a catalyst as providing a lower energy intermediate through which the reaction can proceed, which has the effect of speeding it up or allowing it to occur with less energy input. This is true for all types of catalysis, not just electrocatalysis.

hover over pic for description

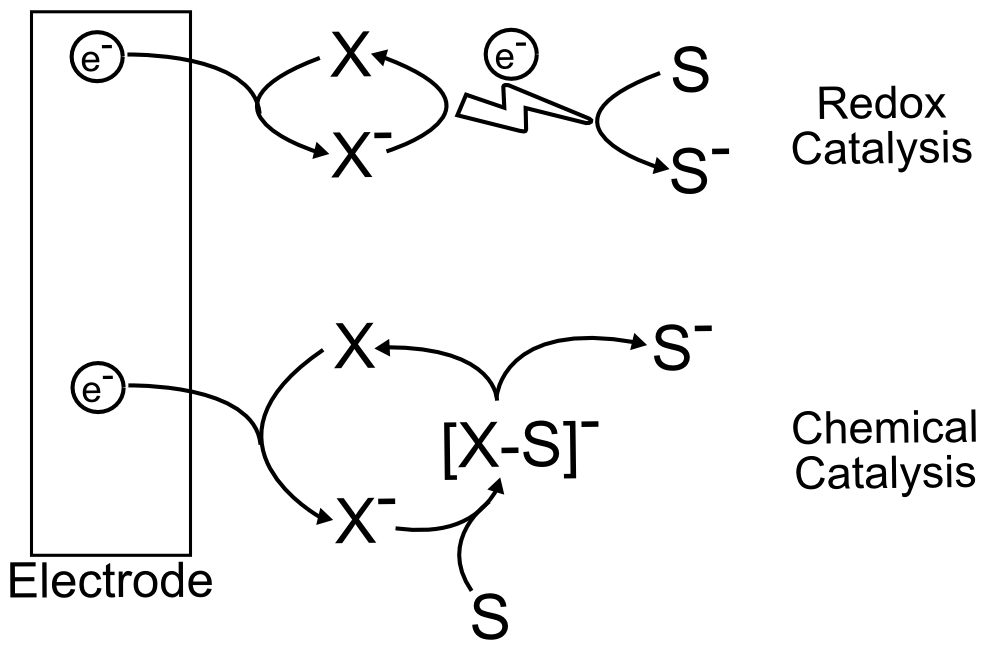

There are two types of molecular electrocatalysts; redox catalysts and chemical catalysts. A redox catalyst is effectively an electron (or hole) shuttle which does not interact with the substrate, whereas chemical catalysts transfer electrons while forming a transient bond with the substrate.

hover over pic for description

Effective redox catalysts are reduced or oxidized at more mild potentials than their target substrates. After “getting charged” at the electrode, they exchange an electron with the substrate molecule and then return to the electrode to repeat the process, resulting in a large catalytic wave. This begs the question, "If the reduction potential of the redox catalyst is at a more mild potential than the substrate, meaning the electron transfer from the catalyst to the substrate is energetically unfavorable, why does catalysis happen?"

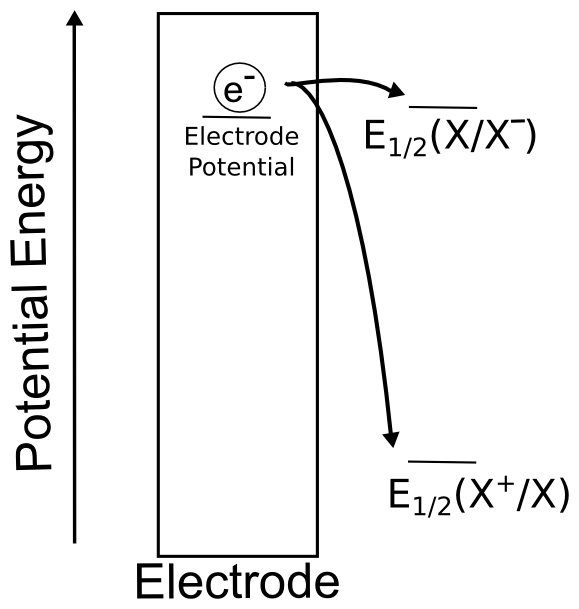

One has to remember that even though the reduction of X may be thermodynamically unfavorable (if the electrode potential is positive of the E0(X/X–) for the reduction), some electron transfer still occurs according to the Nernst equation, and a concentration of X– is present at the electrode surface. What a redox catalyst does is effectively become a “3D electrode”, with an “electrode potential” equal to the E0 of the redox catalyst, by flooding the area near the electrode with charged redox catalyst. Since the “effective area” of the electrode increases, so does the equilibrium concentration of X–, which drives the conversion. The reaction can be driven forward if the electron transfer results in an irreversible chemical step (such as a bond making or breaking). This should be obvious to anyone familiar with LeChatelier’s principle. If you're not familiar with LeChatelier's principle, get familiar with it, it's important for understanding equilibria.

Chemical catalysts perform essentially the same task as redox catalysts, except they form chemical bonds with their substrates in order to drive electron transfer. They often contain redox-active transition metals complexed by ligands. These transition metal complexes can be “activated” by reducing or oxidizing them at an electrode, after which they can proceed to perform the magic that they are known for, by oxidatively adding, reductively eliminating, or serving as a platform on which chemical reactions can easily occur. This leads to multi-step catalysis and more complicated analysis. An easy way to evaluate chemical catalysts is by their effective rate, but through deeper analysis it is possible to tease apart the mechanism and the rate associated with each step.

Screening Catalysts

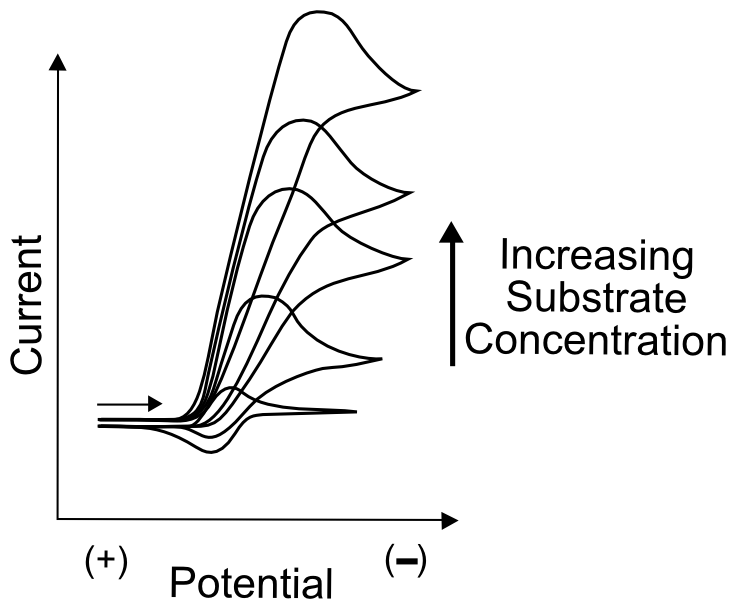

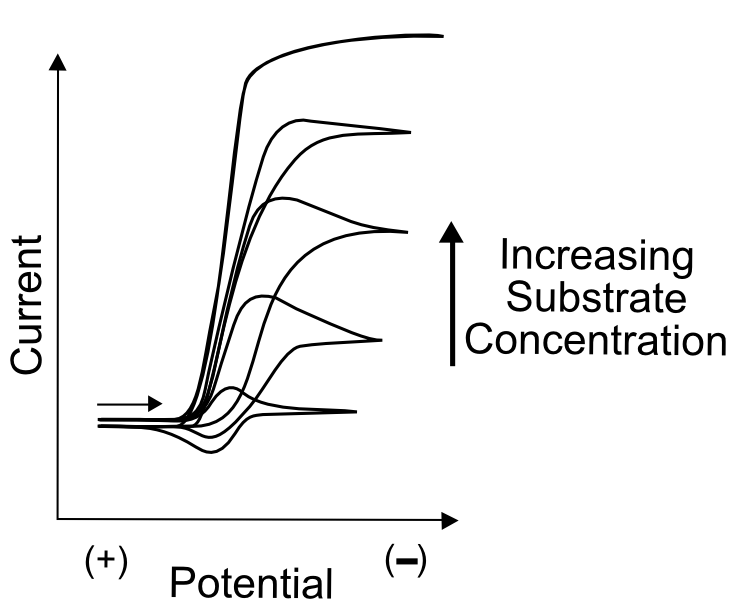

The simplest test to determine whether the “catalyst” might catalyze anything is to compare CVs of the substrate molecule alone, the catalyst molecule alone, and a solution of both. It is extremely important to ensure that the substrate doesn't undergo electron transfer directly from the electrode at the potential where the active catalyst in generated. Meaning that the wave observed in a CV of the substrate alone displays a wave at a more extreme potential than the catalyst molecule. As always, a large amount of data can be obtained by collecting CVs at varying scanrates and, if it's possible to add more substrate without contaminating the solution with unwanted impurities, at a number of different substrate concentrations. In most cases of catalysis, this will result in the continued increase of the "catalytic wave", a substantial increase in current around the potential when the active catalyst (X– in our case) is generated.

hover over pic for description

In many cases, the catalytic wave will seem to grow right out of the wave that generates the active catalyst. If this catalyst feature is reversible in the absence of substrate, the return wave (oxidation of X– back to X) will gradually disappear as more substrate is added. This is due to the fact that, in the case of electrocatalyst X that becomes active as X–, the oxidation of X– can only be observed if X– is stable in solution. In the presence of substrate, X– reacts with a substrate molecule and transfers its electron, becoming X. If enough substrate is in solution, no significant amount of X– can be found near the electrode on the return sweep.

Reasonably fast electrocatalysts (those with a high turnover frequency) will display an increase in current near (even before) the reduction potential at which the catalyst becomes active. This is due to the fact that even before the E1/2 is reached, active catalyst is produced (in concentrations according to the Nernst equation, assuming a reversible electron transfer) at the electrode and may immediately start to react with substrate. Take our X/X– example where X– is the active species that transfers an electron to a substrate, becoming X afterwards. 1% of the catalyst molecules at the electrode will be in the form of X– at 120 mV more positive of its E1/2(X/X–). Even at dilute concentrations, this is millions of millions of molecules, which then react with substrate. If the catalyst rapidly reacts with and transfers an electron to a substrate molecules, more electrons are transferred immediately from the electrode to molecules of X in order to maintain the 1% concentration of X– at the electrode dictated by the Nernst equation. As more substrate diffuses in from the solution, more electrons are transferred to substrate molecules through the catalyst, resulting in increased current before the electrode potential even reaches E1/2.

hover over pic for description

An interesting case to consider is the two electron reduction of a substrate, which is a very common occurrence. Assuming our catalyst X can also exist as X+, a two electron transfer from X– would result in the formation of X+ near an electrode which was at a potential near E1/2(X/X–). The electrode is at a potential where reduction of X+ to X is extremely favorable energetically, and occurs immediately. This drives the rise in current.

hover over pic for description

If the electrocatalyst can tolerate a large excess of substrate, the catalytic wave might plateau instead of peak. A plateau occurs when the reaction is limited not by the diffusion of the catalyst or substrate, but by some other step, such as an electron transfer or a chemical step. Depending on the mechanism of catalysis, information about the rate constants of certain steps can be drawn from the plateau current (ipl), but this is beyond the scope of this text.

hover over pic for description

Shortfalls of Cyclic Voltammetry

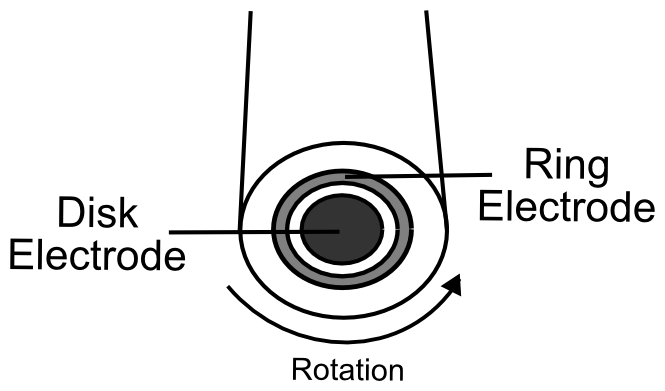

It is important to remember that an increase in current is not necessarily the result of catalysis, as it might be the case that the substrate reacts with the “catalyst” and causes it to decompose, which could result in the release of other redox active fragments and increased current. In order to determine whether catalysis is occurring it is necessary to analyze the products using a rotating ring disk electrode or controlled potential electrolysis (CPE). The researcher should not only confirm the identity of the products using gas chromatography, mass spectrometry, or NMR, but also calculate the faradaic efficiency of the catalyst. The faradaic efficiency is basically the percentage of the electrons that transferred between the working electrode and the desired substrate, it can be found by dividing the number of electrons needed to make the detected amount of product by the total charge passed as measured by the potentiostat.

A rotating ring disk electrode is a like a normal button working electrode, but an additional conductive ring surrounds it. The outer ring is electrically insulated from the working electrode and its potential (voltage) can be controlled by the potentiostat. The ring disk electrode is attached to a special rotator that, as its name suggests, causes the electrode to rotate. This rotation causes the solution to be drawn up to and along the surface of the electrode, meaning that any products from reactions that occur at the center electrode will flow along the surface and some of them will come in contact with the ring. If the products of catalysis are redox active, they can be deteced by the outer ring if it is set to a potential that re-reduces or oxidizes them. For example, if you suspect that hydrogen (H2) is the product of catalysis, running a CV (scanning the potential) of the inner working electrode while holding the potential of the ring electrode at a potential that can oxidize H2 should display oxidation current at the ring electrode immediately after reduction current is observed at the center disk electrode. Using a known, redox active molecule such as ferrocene, you can figure out the maximum amount of material generated at the center electrode can be detected by the ring. This allows one to get a rough estimate of the faradaic efficiency of the catalyst.

hover over pic for description

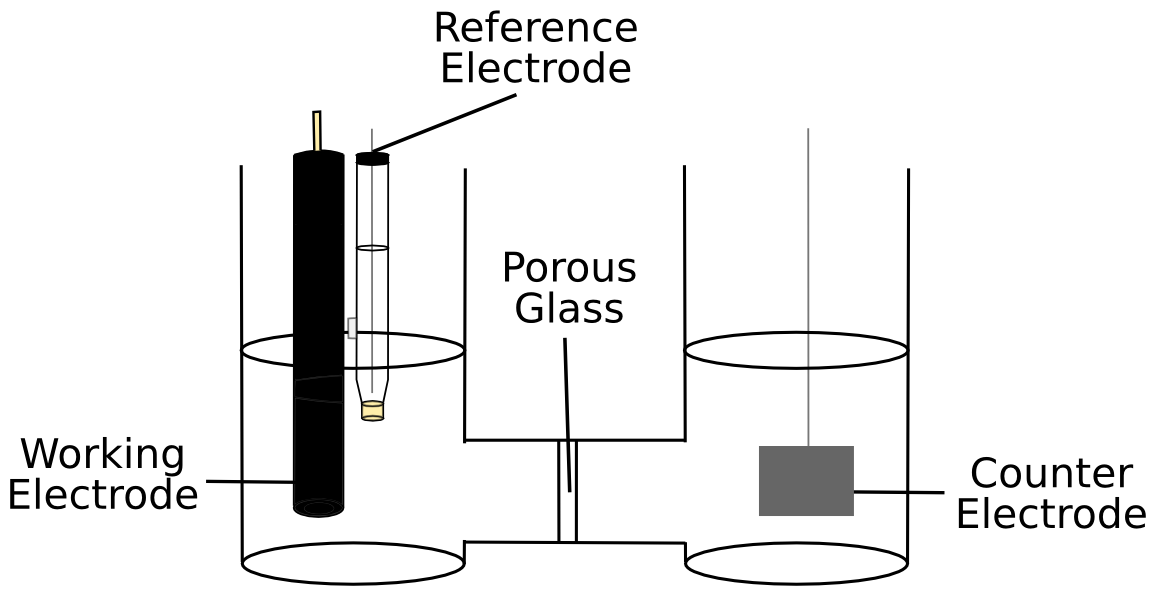

Controlled potential electrolysis, sometimes called "bulk electrolysis," is a relatively simple technique. The working electrode is placed in a solution containing catalyst and substrate and held at a potential where catalysis occurs. When performing CPE, it is necessary to use a two compartment cell in order to separate the working electrode and the counter electrode, as anything reduced (or oxidized) at the working electrode will be re-oxidized (or re-reduced) if it comes in contact with the counter electrode. Methods of product analysis includes gas chromatography (if the product is a gas), mass spectrometry, or nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. A magnetic stirbar can be added to intentionally move catalyst and substrate to help the CPE occur faster. If quantitative methods are available to measure the amount of product that is produced from electrocatalysis, it is possible to measure the faradaic efficiency of the catalyst by simply dividing the product of the number of electrons that are needed to form one product molecule and the amount of product by the number of electrons passed during the CPE.

hover over pic for description

Did I earn one of these yet?

is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.